Hillside/United Way Program Builds Career Connections for Syracuse Youth

By Renée K. Gadoua

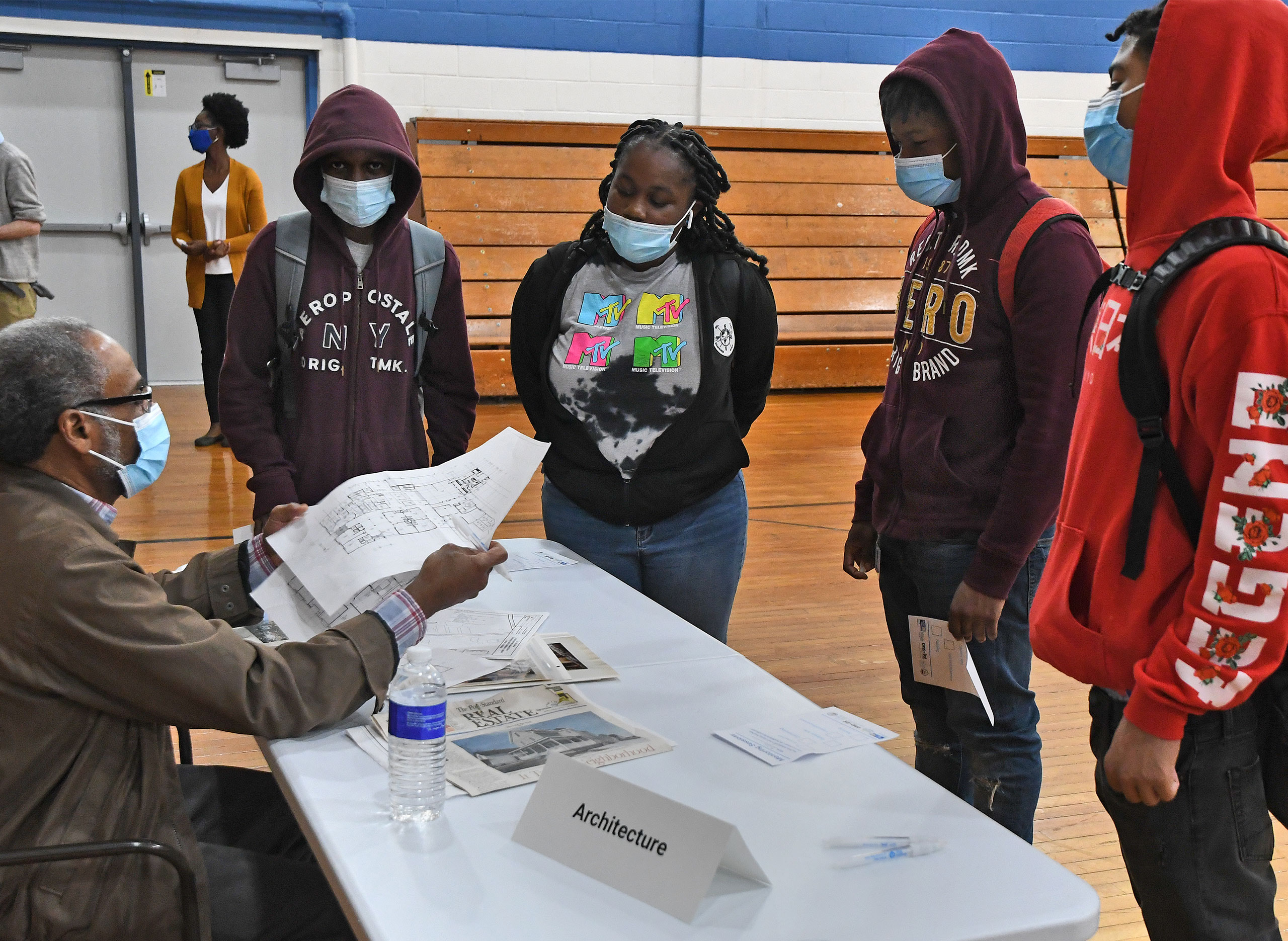

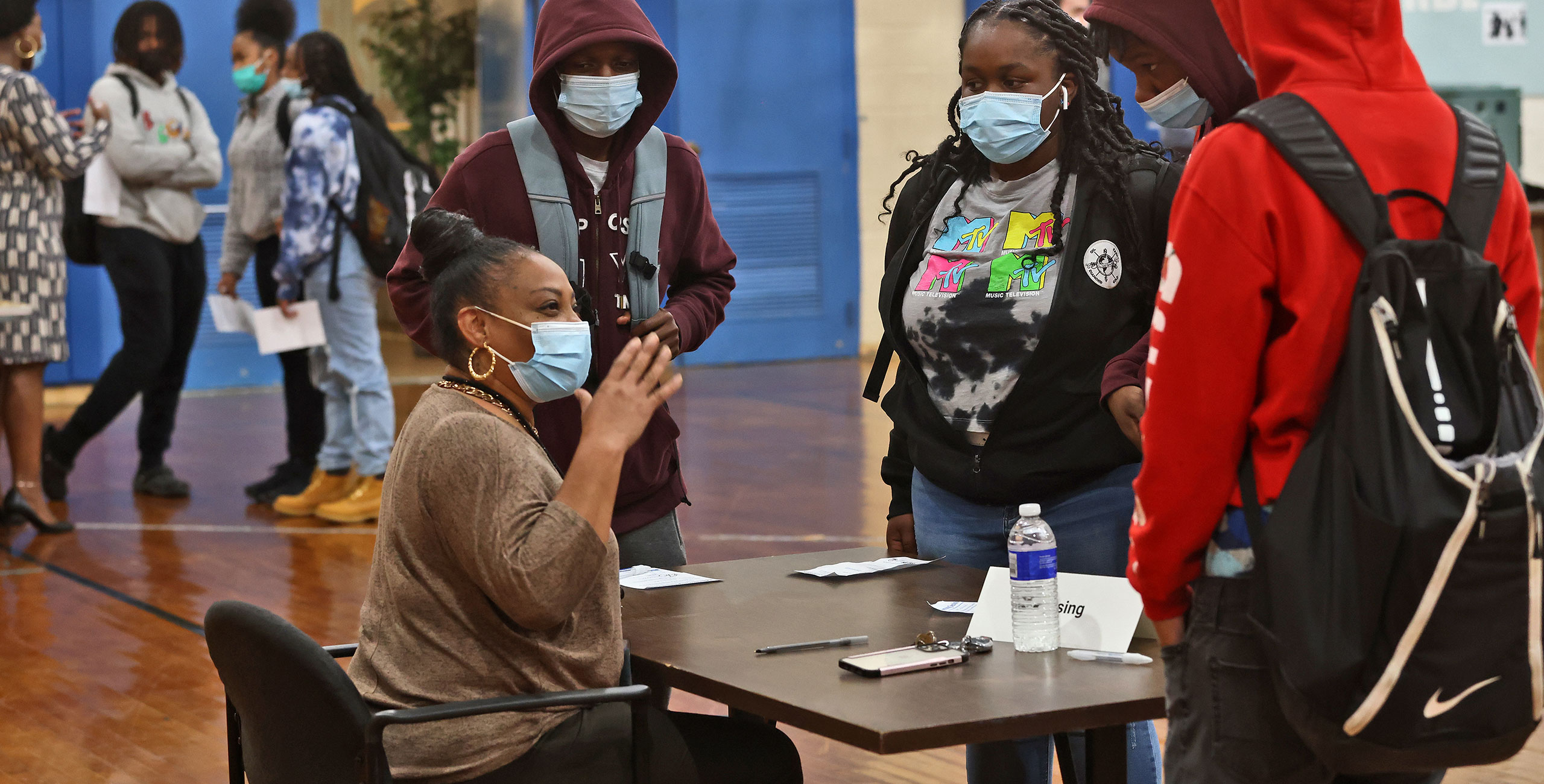

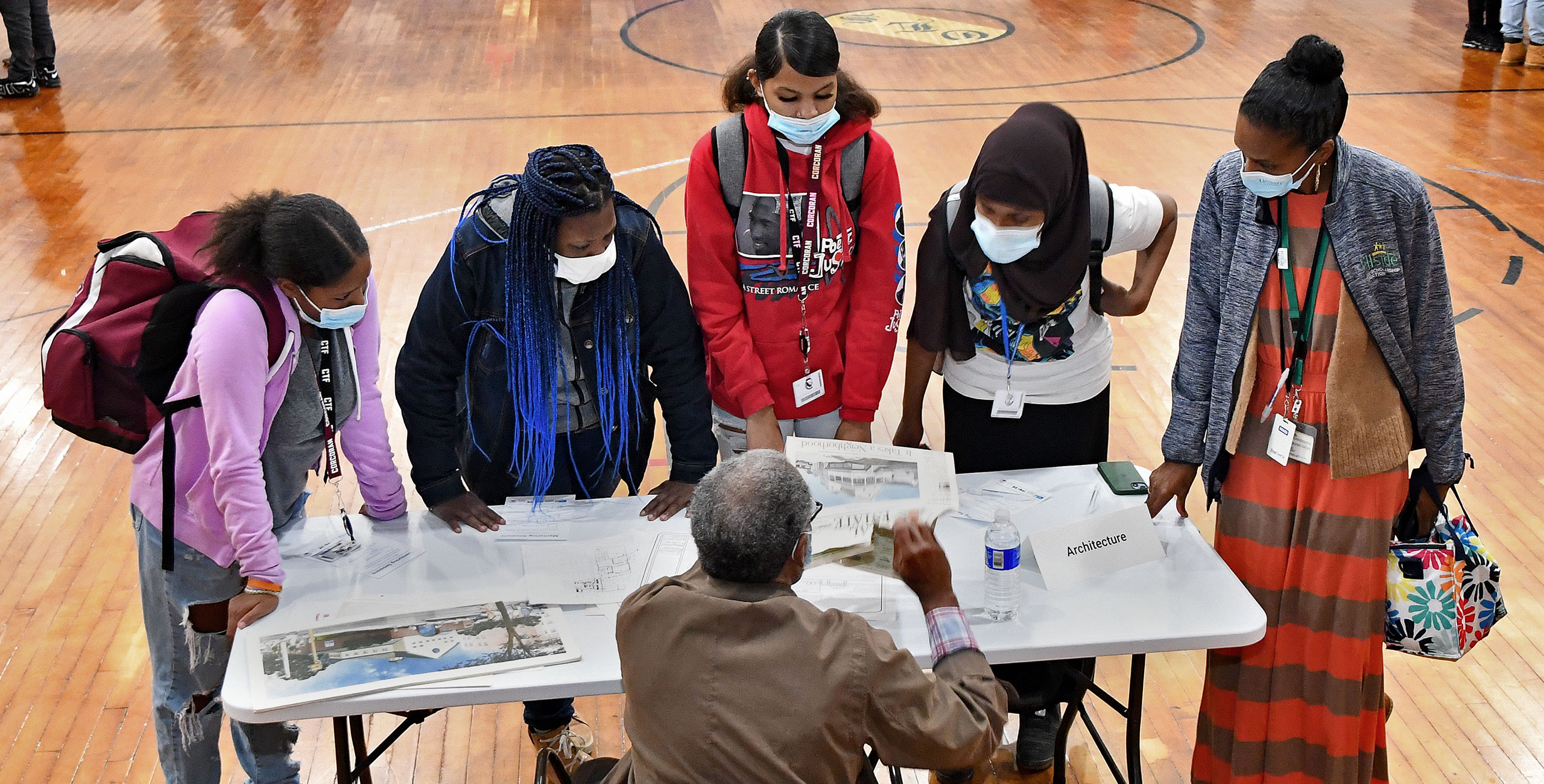

When Syracuse architect Kenel Antoine shared drawings, blueprints and photos at a recent Hillside Work-Scholarship Connection program, some 7th- to 12th-grade students recognized his projects. “They said, ‘Oh, I know this house. I know this church,’” he said. “They were able to connect what an architect does with something concrete they can see and view and appreciate.” Karinda Shanes, regional executive director of Hillside Work-Scholarship Connection (HWSC) said staff had to drag students from some career sessions — including Antoine’s. “Some kids you really had to pull away from a speaker,” she said. “Just observing kids were still lingering let us know we had the right people and were engaging the students’ minds.”

Shanes hopes the program, supported by United Way of Central New York, planted career ideas for Syracuse students who attended one of four sessions in fall 2021 and March 2022. The mentoring sessions HWSC’s improving high school graduation rates, and helping students realize their potential.

“We want to help students think about their next stage,” Shanes said. “A lot of our kids are struggling in their junior year and have no plans after graduation. We want to help them think about whether they want to pursue a two-year college, a four-year college, a job or the military.”

Hillside worked with United Way to recruit professionals to discuss their careers with students and provide a broad view of options they may never have considered. “It’s a persistent misconception that not going to college means you cannot have a good paying job,” Shanes said. “We wanted our speakers to have engaging conversations about their fields. The jobs may require education or may need technical skills, or they may get training from the employers.”

Hillside students, many of whom started in the afterschool program as seventh graders, suggested occupations for the mentoring program. They were interested in culinary arts, nursing, architecture, cosmetology and law enforcement. They also wanted to hear about working as a dog groomer or an EMT.

“A lot wanted to know about manufacturing,” Shanes added. “Our kids think manufacturing is dirty, grungy, low pay for standing at a machine all day. It’s not.”

Students also need mentors who look like them. “We try to bring in Black and brown professionals so people can connect and find it relatable,” Shanes said. “If they meet a caring adult and can talk to you and trust you and can build a relationship, they’ll talk to you.”

At the mentoring program, students rotated among six stations. Shanes wasn’t surprised students were interested in talking with cosmetology and nursing professionals — especially presenters who brought props and outgoing personalities. She was pleasantly surprised at their interest in architecture.

“They liked his visuals and his calm and collected demeanor,” she said of Antoine. “He had things to show that they could see a change from one blueprint to another. You don’t find too

many people of color in that profession. If they could just be introduced and see there was something relevant to them, it might spark their interest.”

Antoine, a native of Haiti who studied architecture at Syracuse University and earned a master’s degree from the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, “talked to them about the kind of work I was involved in and how I got into the profession.” He also “told them things I like about the profession and certain things I discovered about the profession and myself.”

Drawing ability and comfort with geometry — “That’s how we create space” — belong in the architect’s toolbox, he said. But the most important tool is imagination. “Before you create something, you have to imagine it,” Antoine said. “Very often, before I put anything on paper, I’m imaging it. I’m walking through it in my mind.”

He also shared the downsides of the profession: education and training are hard; it’s a competitive field, and most architects don’t make a lot of money. “You go into it not so much for the money, but for the love of it,” Antoine said. “The best thing is when you create something and people see it.”

HWSC serves more than 1,200 students from 14 Syracuse schools each year. “It’s more than college and career readiness,” Shanes said. “We’re always looking to broaden the horizons of the whole person.” Thinking about life after high school, she explained, starts with questions like Do you like animals? Do you like to cook? Do you like cars?

The career sessions are a natural step in those discussions. “We’d like to have these businesses offer tours at their facilities so students can see what it’s like in the buildings,” she said. Relationships with employers and professionals could eventually lead to job shadowing, internships or entry-level jobs, she said.

Nan Kern Eaton, president of United Way of Central New York said, “We realized for people to choose to go to school and think about architecture or engineering, we need to engage with people in seventh and eighth grade so they can meet an architect. Do you like to draw? Do you like to build things? If so, maybe you can be an architect.”

United Way supports expanding educational and employment opportunities for at-risk youth.

“People of color are overrepresented in poverty,” Eaton said. “We thought about occupations that have low representations of people of color, like architects. Just because you don’t know anyone in that field doesn’t mean you can’t do it. I really want kids to see their own natural gifts and see they have so much to offer the world.”

Shanes describes the program’s goals as both inspirational and practical. “The workforce is in a crisis,” she said. “We need kids to understand that they could get tech skills and go on to these full-time jobs. We have to embrace the fact some of our kids are not college bound, but they can be productive members of society.”

Renée K. Gadoua is a writer and editor living in Manlius.